On the International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women, it is important to throw light on a growing threat women journalists are facing today: The insidious problem of online violence is increasingly spilling offline, with potentially deadly consequences.

In a global survey of 1,200 media workers, conducted by the International Center for Journalists (ICFJ) and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), some 20 percent of women journalists and media workers reported being targeted with offline abuse and attacks that they believe were connected with online violence they had experienced.

These preliminary research results also point to a surge in rates of online violence against women journalists. Nearly three-quarters – 73 percent – of participants identifying as women said they have experienced online abuse, harassment, threats and attacks.

Online violence is the new front line in journalism safety – and it is particularly dangerous for women. They – just like women across society – experience higher levels of harassment, assault and abuse in their daily lives. women journalists are also at much greater risk in the course of their work, especially on digital platforms. In the online environment, we see exponential attacks – at scale – on women journalists, particularly at the intersection of hate speech and disinformation.

Alarmingly, the risk extends to their families, sources and audiences. Online attacks against women journalists are often accompanied by threats of harm to others connected to them, or those they interact with, as a means of extending the “chilling effect” on their journalism.

In combination, misogyny and online violence are a real threat to women’s participation in journalism and public communication in the digital age. This is both a genuine gender equality struggle and a freedom of expression crisis that needs to be taken very seriously by all actors involved. We believe that collaborative, comprehensive, research-informed solutions are increasingly urgent.

Our finding that a fifth of the women journalists who responded to our survey reported experiencing abuse and attacks in the physical world that they believed were associated with online violence targeting them is particularly disturbing. It underlines the fact that online violence is not contained within the digital world.

In 2017, the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) reported that in at least 40 percent of cases, journalists who were murdered reported receiving threats, including online, before they were killed, “highlighting the need for robust protection mechanisms”. The same year, two women journalists on opposite sides of the world were murdered for their work within six weeks of one another: celebrated Maltese investigative journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia and prominent Indian journalist Gauri Lankesh. Both had been the targets of sustained gendered online attacks before they were murdered.

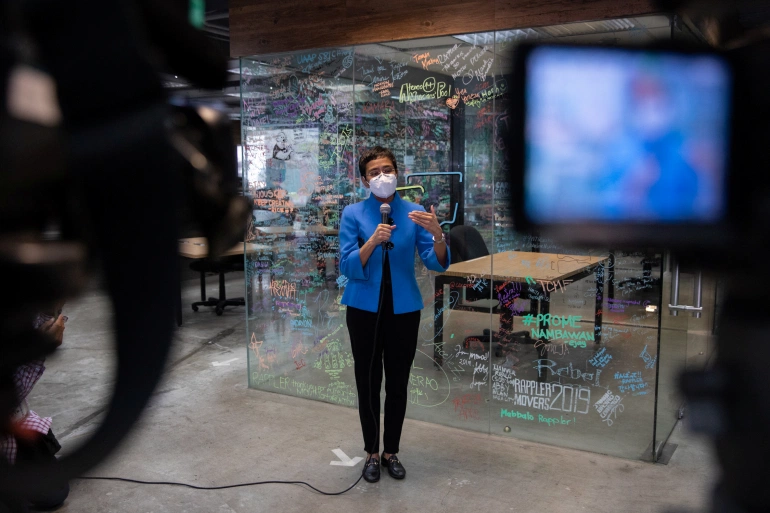

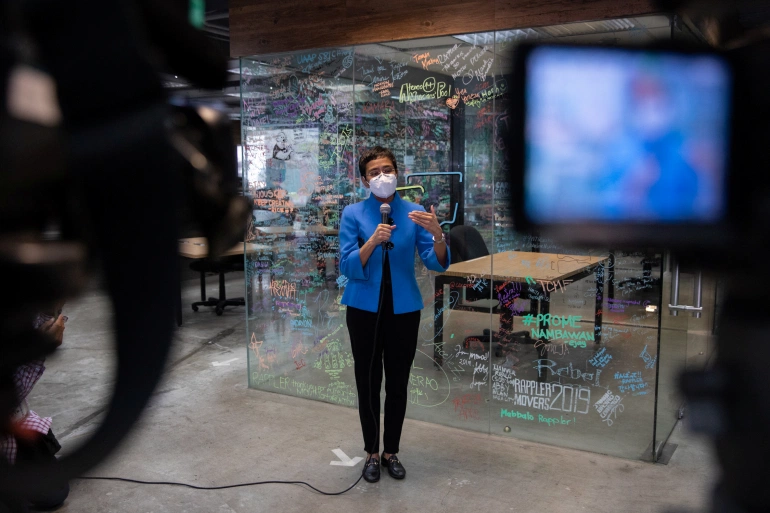

Parallels between patterns of online violence associated with Caruana Galizia’s death and attacks being experienced by another high-profile target – Filipino American journalist Maria Ressa – are so striking that the murdered journalist’s sons issued a public statement expressing their fears for Ressa’s safety. “This targeted harassment, chillingly similar to that perpetrated against Ressa, created the conditions for Daphne’s murder,” they wrote.

Likewise, the death of Lankesh, which was associated with online violence propelled by right-wing extremism, also drew international attention to the risks faced by another Indian journalist who is openly critical of her government: Rana Ayyub. She has faced an onslaught of rape and death threats online alongside false information campaigns designed to counter her critical reporting, discredit her, and place her at greater physical risk.

Pointing to the emergence of a pattern, the targeting of Ayyub led five UN special rapporteurs to intervene in her defence. Their statement drew parallels with Lankesh’s case, and called on India’s political leaders to act to protect Ayyub, stating: “We are highly concerned that the life of Rana Ayyub is at serious risk following these graphic and disturbing threats.”

This trend of online attacks against women journalists only appears to be increasing over time. Back in 2014, when these issues first began to attract mainstream media attention, a survey of nearly 1000 women journalists conducted by the International Women’s Media Foundation (IWMF) and the International News Safety Institute (INSI), which was supported by UNESCO, found that 23 percent of women respondents had experienced “intimidation, threats or abuse” online in relation to their work.

A follow-up survey conducted by IWMF and Trollbusters in 2018, involving a smaller but still substantial sample, found that 63 percent of women respondents had been harassed or abused online at least once. And in our survey, 73 percent of women reported experiencing online abuse, harassment, threats and attacks. Although these surveys are not directly comparable, viewed collectively they point to a disturbing pattern.

The COVID-19 pandemic and social media risks

Physical violence against women has increased during the COVID-19 pandemic in what has been called the “shadow pandemic”. At the same time, online violence against women journalists also appears to be on the rise. In another global survey, conducted earlier this year by ICFJ and the Tow Center for Digital Journalism at Columbia University, 16 percent of women respondents said online abuse and harassment was “much worse than normal”.

This finding likely reflects the escalating levels of hostility and violence towards journalists seen during the pandemic – fuelled by populist and authoritarian politicians who have frequently doubled as disinformation peddlers. Significantly, one in 10 English-language respondents to the ICFJ-Tow Center’s survey indicated that they had been abused – online or offline – by a politician or elected official during the first three months of the pandemic.

Another relevant factor is that the “socially distanced” reporting methods necessitated by coronavirus have caused journalists to rely more heavily on social media channels for both newsgathering and audience engagement purposes. And these increasingly toxic spaces are the main enablers of viral online violence against women.

This conundrum – the need for women journalists to participate in online communities to do their jobs, even as these spaces grow increasingly unsafe – has become more urgent over time. The 2014 INSI-IWMF survey found that 88 percent of respondents felt their work had grown more dangerous because of the advent of social media and its role in audience engagement and news distribution.

Since then, research has increasingly focused on the role and responsibility (or lack thereof) of social media companies as facilitators of online violence against women journalists. Several studies have concluded that some women journalists are withdrawing from front-line reporting, removing themselves from public online conversations, quitting their jobs, and even abandoning journalism in response to their experience of online violence.

There is even evidence of women journalism students being deterred from pursuing a career in the field because of their experiences of online toxicity, or their knowledge of the risks of exposure to online violence in the course of their work. In parallel, this crisis is making women sources less likely to speak online and we have also seen evidence of the retreat of women audiences from online engagement.

However, there have also been numerous cases of women journalists fighting back against online violence, refusing to retreat or be silenced, even when speaking up has made them bigger targets.

What can be done now to respond to this crisis?

It is vitally important for news organisations to have gender-sensitive policies, guidelines, training, and leadership responses. Together, these measures must ensure awareness of the problem, build the capacity to deal with it, and trigger action to protect women journalists in the course of their work. These strategies also need to be connected and holistic in the sense that they bridge physical, digital and psychological threats, and address them accordingly.

We know that physical attacks on women journalists are frequently preceded by online threats made against them. These can include threats of physical or sexual assault and murder, as well as digital security attacks designed to expose them to greater risk. And such threats – even without being followed by physical assault – often involve very real psychological impacts and injuries.

So, when a women journalist is threatened with violence online, this should be taken very seriously. She should be provided with physical safety support (including increased security when necessary), psychological support (including access to counselling services), and digital security triage and training (including cybersecurity and privacy measures).

But she should also be well supported by her editorial managers, who need to signal to staff that these issues are serious and will be responded to decisively, including with legal and law enforcement intervention where appropriate.

The stigma needs to be removed from feeling and expressing the impacts of online violence. In particular, we need to be very cautious about suggesting that women journalists should build resilience or “grow a thicker skin” in order to survive this work-related threat to their safety.

They are being attacked for daring to speak. For daring to report. For doing their jobs. The onus should not be on women journalists to “just put up with it”. The question that needs to be asked instead is: How do we protect women journalists from exposure to such violence in the course of their work, or at least minimise it?

The answers ultimately lie not in temporary measures like requiring them to retreat from digital journalism practices, including audience engagement. The solutions lie in structural changes to the information ecosystem designed to combat online toxicity generally and exponential attacks against journalists, in particular.

This will require rich and powerful social media companies living up to their responsibilities within international human rights frameworks, which are explicitly designed to protect press freedom and secure journalism safety. It will also require them to deal decisively, transparently and appropriately with disinformation and hate speech on the platforms as they affect journalists.

This will likely mean that these companies need to accept their function as publishers of news. In doing so, they would inherit an obligation to improve their audience curation, fact-checking and anti-hate speech standards. Regulatory work is also likely to be a feature of this process.

Ultimately, collaboration and cooperation that spans big tech, newsrooms, civil society organisations, research entities, policymakers and the legal and judicial communities will be required. Only then can concrete action be pursued.

Authors’ note: The survey results are non-generalisable because they are based on a self-selecting group of journalists and other media workers. The survey is part of an ongoing global study commissioned by UNESCO.

Johann Petrak assisted with data analysis for this article. He is a Research Fellow in the Department of Computer Science at the University of Sheffield. Dr Pete Brown, Research Director at the Tow Center for Digital Journalism at Columbia University, conducted the quantitative analysis of the data presented from the Journalism and the Pandemic Project.

Jackie Harrison Professor Jackie Harrison is Chair of the Centre for Freedom of the Media (CFOM) at the University of Sheffield and UNESCO Chair on Media Freedom, Journalism Safety and the Issue of Impunity.

Julie Posetti Dr Julie Posetti is Global Director of Research at the International Center for Journalists, where she leads the UNESCO-commissioned online violence project.

Silvio Waisbord Silvio Waisbord is Director and Professor in the School of Media and Public Affairs at the George Washington University.

World Opinions Débats De Société, Questions, Opinions et Tribunes.. La Voix Des Sans-Voix | Alternative Média

World Opinions Débats De Société, Questions, Opinions et Tribunes.. La Voix Des Sans-Voix | Alternative Média