Politicians know that they have a problem when they have to deny it. On Monday, Vladimir Putin insisted that an extravagant palace on the Black Sea coast did not belong to him, following a video exposé released by the opposition leader, Alexei Navalny, and so far watched by around 90 million people. Footage of him swimming in a giant pool was fake.

Nothing described as his property there either “belongs to or ever belonged to me or my close relatives. Ever”, Mr Putin said. (His opponent has said that the estate formally belongs to four proxies.)

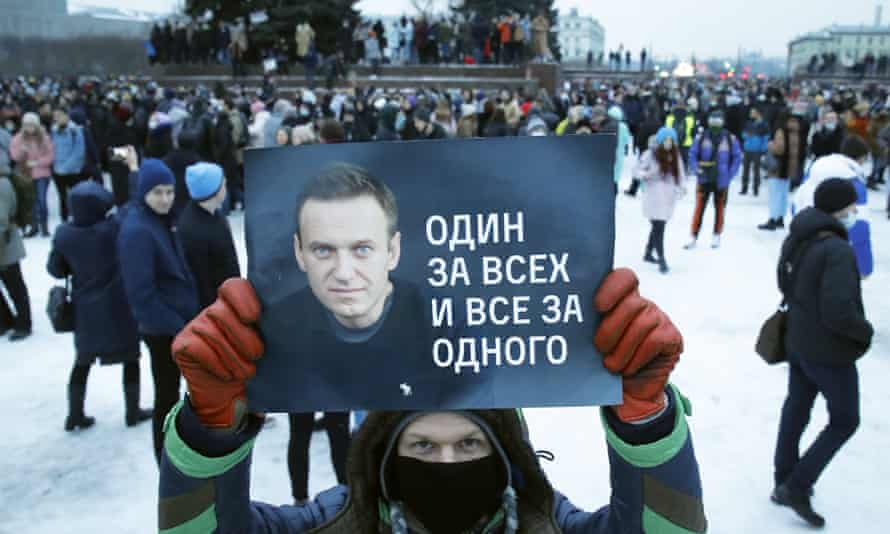

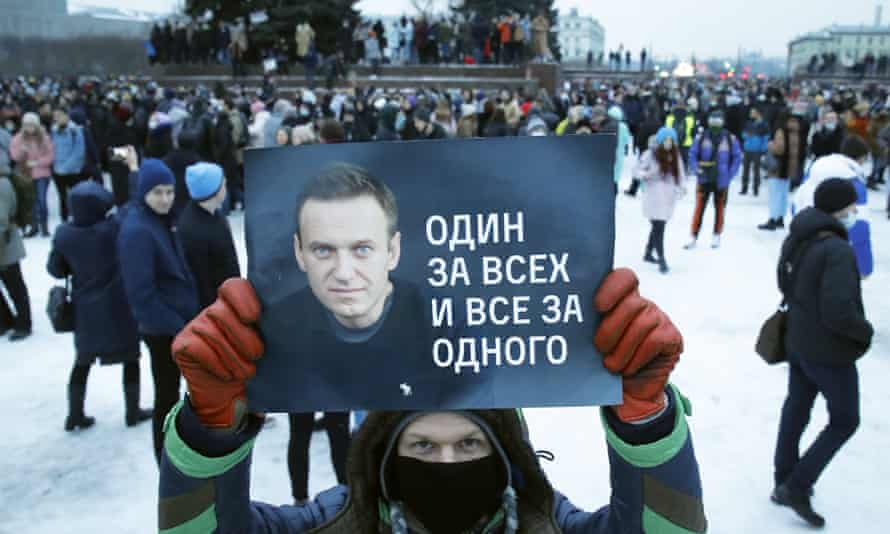

The Russian president and his allies have preferred to publicly ignore Mr Navalny. Now, they are attacking him and his claims head-on, and denouncing the protests he has inspired as illegal and dangerous. Tens of thousands took to the streets in more than 100 cities across the country on Saturday, in the largest show of opposition for years – prompting police to arrest thousands, including Mr Navalny’s wife, Yulia, and many of his allies.

The demonstrations were sparked primarily by Mr Navalny’s arrest on his return to Russia, following treatment in Germany after the suspected FSB assassination attempt. He could be sent to a penal colony, perhaps for years, by the end of this month.

His extraordinary courage, charisma and savvy social media tactics – as well as shock at the novichok poisoning (for which officials say there is no evidence) – have brought support from disparate parts of the Russian opposition, many of whom may not share his broader political outlook. Mr Putin’s approval ratings still appear high, but are well below their peak. Underlying these protests are frustration at poor standards of living and the dismal economic situation, worsened by low oil prices and the pandemic, as well as resentment at corruption and other political abuses. In many places, local issues have fused with wider complaints.

More protests have been called for this weekend, ahead of Mr Navalny’s court hearing. In 2013, he escaped a prison sentence thanks to public pressure. This time, the scale of opposition has rattled the Kremlin, and the uprising that began in Belarus last summer has sharpened anxieties. Mr Navalny, long a nuisance, now looks like a threat. Assaults, pressure on his family, jail and even poisoning have failed to silence him. Keeping him behind bars would keep him quiet, while warning off others. But supporters hope the protests will at least help to maintain attention on his case – and, perhaps, safeguard him while in custody.

The US, EU and UK have rightly called for his immediate and unconditional release. The EU foreign policy chief, Josep Borrell, says that he will press the case in Moscow next month. Whether action results – or amounts to more than largely symbolic sanctions – is another matter. Germany is determined to press ahead with the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline, despite growing opposition in Europe and sanctions imposed by the US.

Angela Merkel said last week that the attack on Mr Navalny had not changed her basic view of the project. The UK has done embarrassingly little to crack down on money laundering by close friends of the Kremlin. A damning report from the intelligence and security committee last year called the City of London a “laundromat” for illicit funds. Britain’s unexplained wealth orders – introduced in 2018 – could, and should, be used more effectively.

Russian officials and state media are already busy portraying Mr Navalny as a western stooge, though he has always been careful to keep his distance from foreign governments. Mr Putin’s real problem is not his jailed opponent, but the Russian people whose dissatisfaction he harnesses. Their daily experiences do as much to erode the Kremlin’s authority as Mr Navalny’s viral videos. While the president may prefer to ignore it, there is no denying public discontent.

World Opinions Débats De Société, Questions, Opinions et Tribunes.. La Voix Des Sans-Voix | Alternative Média

World Opinions Débats De Société, Questions, Opinions et Tribunes.. La Voix Des Sans-Voix | Alternative Média