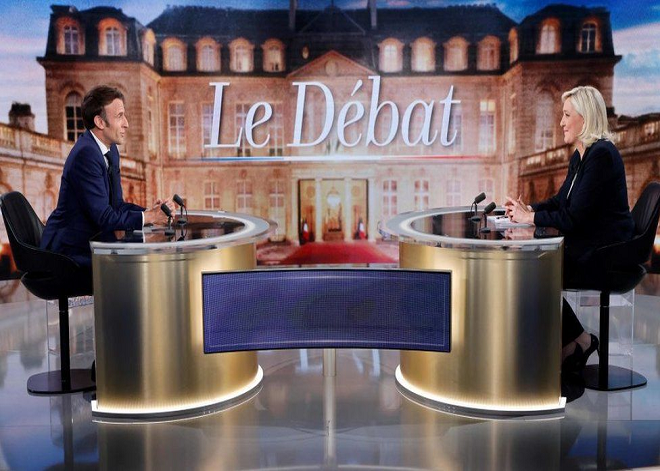

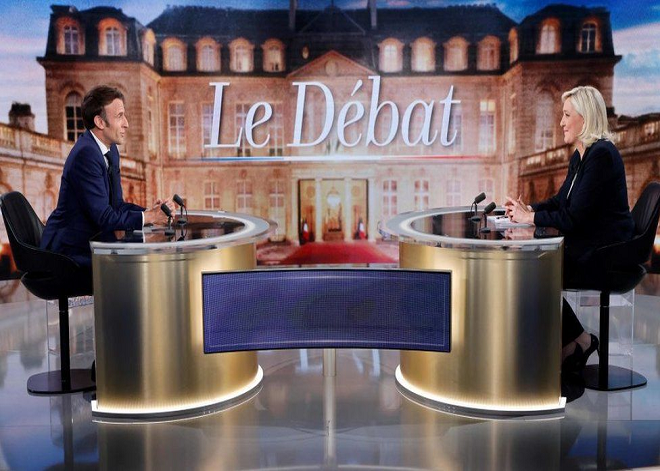

Four days before France votes on its next president, the two remaining candidates are going head to head in their only televised debate.

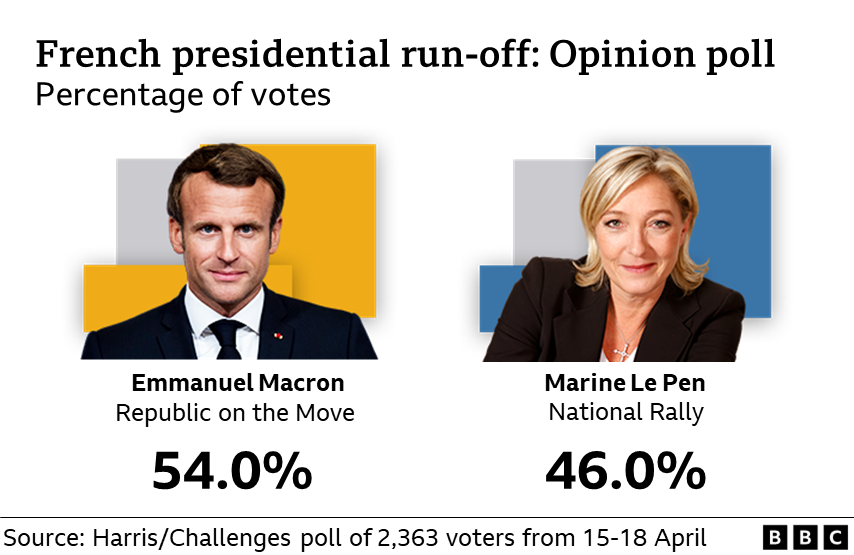

Far-right leader Marine Le Pen has fallen behind Emmanuel Macron in the opinion polls but millions of voters are still undecided.

It did not take long for the two-and-a-half hour clash to burst into life.

The two candidates confronted each other’s record and policies on the cost of living and relations with Russia.

Spiralling prices of energy and at the shops have dominated the campaign and immediately took centre stage in the debate, broadcast on the two biggest TV networks as well as the big news channels.

Emmanuel Macron was widely seen as the winner of the 2017 debate, when his rival appeared flustered and underprepared. But this time, Marine Le Pen was ready from the start.

As the encounter began, Ms Le Pen said 70% of the French people believed their standard of living had fallen over the past five years and she would be the president of civil peace and national brotherhood.

Mr Macron said France had known unprecedented crisis, with Covid followed by war in Europe. He had steered France through those challenges and aimed to make France a stronger country, he said. After a relatively civil start, the debate quickly turned combative.

Hot-button issues in debate

Cost of living: The debate, hosted by prominent TV journalists Léa Salamé and Gilles Bouleau, was set to cover eight main themes from cost of living to social and international issues, but it was energy prices and other increasing costs that the two candidates clearly wanted to tackle first.

It is one of Marine Le Pen’s strong points and she said from the start that it was a priority: « I will permanently cut VAT on energy. I will also cut taxes, no income tax for under-30s ». She accused Mr Macron on letting pension levels fall in real terms too.

Mr Macron said his solution was to impose a cap on prices which was « twice as effective as dropping sales tax ».

After a calm start the two candidates quickly became more animated as they disagreed on how to bring down energy prices. Mr Macron repeatedly challenged his opponent’s proposals as unworkable. She snapped back: « I want to give the French their money back. »

International relations: Russia’s war in Ukraine was the second big issue of the night. Emmanuel Macron said Russia was « going down a fatal path » and the role of France and Europe was to provide Ukraine with military equipment and take in refugees.

Ms Le Pen, who has been criticised for her close ties to the Kremlin and for taking a Russian bank loan for her party, warned that giving Ukraine weapons could make France a « co-belligerent ». However, she supported her opponent’s policy of backing Ukraine and taking in refugees.

At this point Mr Macron went on the offensive, pointing out that she was one of the first political leaders in 2014 to recognise Russia’s annexation of Crimea. « You’re speaking to your banker when you speak to Russia, » he said.

Ms Le Pen said she had taken Russian money as no French bank would lend to her party. When she argued that she had had to borrow money like millions of French people, he countered that the French did not look to Russia for finance.

European Union: Marine Le Pen has changed her policy from leaving the EU to now seeking change from within it. But Mr Macron argued that her idea of a « Europe of nations » would spell the end of the EU and that « you are selling a lie ».

She said that in the current EU France was failing to defend its interests and she would stop negotiating trade deals « hurt French producers and farmers ».

Retirement age and pensions: The debate then moved on to one of the biggest issues of the election. Emmanuel Macron has said France needs to raise the pension age from 62 to 65 over nine years, while Ms Le Pen wants to keep it at 62.

Ms Le Pen said raising the pension age to 65 was « absolutely intolerable ». He hit back saying she was promising to be more generous with pensioners but did not explain how she would pay for it. She argued his economic record was very poor and ironically referred to an old nickname as « Mozart of finance ».

Significance of debate

Televised confrontations between the top two candidates have been a highlight of French presidential elections for almost five decades. The last debate attracted 16.5 million viewers so it could play a crucial role with undecided voters.

The TV duels have proved most decisive when the polls are close. In 1974, conservative Valéry Giscard d’Estaing went on to beat Socialist François Mitterrand after performing well in their debate. Mitterrand did better in the rematch in 1981 and won the run-off vote.

And this is the first time since then that the same candidates have squared off in two consecutive elections.

The 2017 debate was a disaster for Ms Le Pen and she was trounced in the run-off, winning only a third of the vote.

This time around the race is much closer and a strong performance by Ms Le Pen could win over a big section of undecided voters. She halted her campaign on Monday to concentrate on the debate and her rival is unlikely to have as easy a ride as five years ago.

The gap in the opinion polls has widened slightly since the first round vote in which the incumbent president won 27.85% and Ms Le Pen came second with 23.15%. But they are still fluctuating wildly, suggesting Mr Macron will secure between 53% and 57% of the vote.

Marine Le Pen needs to perform far better than in 2017 to have a chance of victory. Both the debate and the race appear to be her rival’s to lose.

What the candidates stand for

The choice for voters is far clearer than five years ago, when Emmanuel Macron won with very little experience as a politician.

His strict Covid policies alienated many voters and he has been accused of acting as a « president for the rich ». He is more popular in the big cities but has secured the support of other mainstream left and right parties for his pro-EU liberal and global outlook.

Marine Le Pen has toned down her nationalist, anti-EU rhetoric but she still plans to revise France’s relationship with the European Union and Nato. She is traditionally more popular in rural, poorer areas.

World Opinions – BBC News

World Opinions Débats De Société, Questions, Opinions et Tribunes.. La Voix Des Sans-Voix | Alternative Média

World Opinions Débats De Société, Questions, Opinions et Tribunes.. La Voix Des Sans-Voix | Alternative Média