“The only ones for me are the mad ones,” begins Jack Kerouac’s famous sentence. “The ones who are mad to live, mad to talk, mad to be saved, desirous of everything at the same time” — you know the rest.

For some, though, the only ones are the shy ones. The rumpled, the abstracted, the easily crushed, the not quite made for this world — the word people, and not the glamorous sort: lexicographers, copy editors, fact checkers, librarians, the better sort of Wikipedia updaters: the rank and file of the intellectual proletariat.

These unacknowledged legislators of the world of reading matter, this band of shaggy-sweatered warriors, share expertise and a nomenclature and a tendency to blink in strong sunlight.

Now that scorn for knowledge has been spread in America, like a squirt from a pump dispenser of liquid margarine, Evelyn Waugh’s instruction has never sounded more necessary: “Pray always for all the learned, the oblique, the delicate. Let them not be quite forgotten at the throne of God when the simple come into their kingdom.”

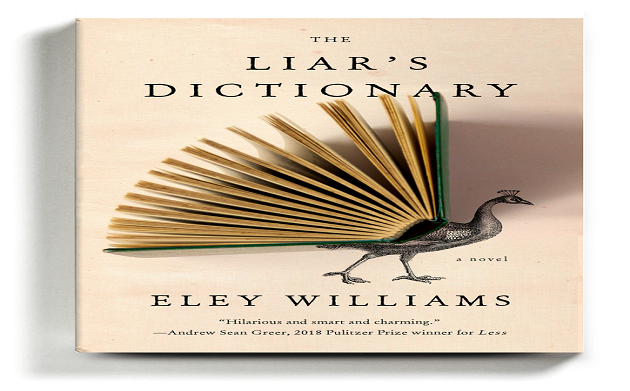

The English writer Eley Williams’s spirited first novel, “The Liar’s Dictionary,” is about lexicography. It’s a celebration of the people who compile dictionaries, even if they’re driven out of their minds in the process.

Dictionaries are plump and (mostly) written in earnest. This novel more resembles a bonsai tree — compact, wizened and funny. It’s about fricatives and vowels and Latin and love; it’s about updating the meanings of words like “dyke,” “teabag” and “marriage.” Its idea of a joke is to remark that someone looks like they’ve been hit by an omnibus.

Williams is a fellow of the Royal Society of Literature and the author of a previous book, “Attrib.,” a collection of word-besotted short stories. In that book a woman worries about giving her cat fleas, instead of the other way around.

“The Liar’s Dictionary” tells braided stories. It’s about two sets of characters, living in London more than a century apart. Each set toils on Swansby’s New Encyclopaedic Dictionary, most notable for having never been completed, though an edition was published in the 1930s.

This endearingly hapless (and wholly fictional) dictionary has long dwelled in the shadow of what Williams calls “those sleek dark blue hearses” — the Oxford English Dictionary and the Encyclopaedia Britannica.

The book rewinds to the 19th century, where a shy, bow tie-wearing man with a weird secret (he speaks with a fake lisp) works on the letter “S” of Swansby’s dictionary. His name is Peter Winceworth. He chafes at the pinning down of language. For fun he begins to insert mountweazels — bogus entries — into the dictionary.

By Dwight Garner – nytimes.com

World Opinion | Alternative Média زوايا ميادين | صوت من لا صوت له Débats De Société, Questions, Opinions et Tribunes.. La Voix Des Sans-Voix | Alternative Média

World Opinion | Alternative Média زوايا ميادين | صوت من لا صوت له Débats De Société, Questions, Opinions et Tribunes.. La Voix Des Sans-Voix | Alternative Média