I took a look at Obama’s new memoir and found the man in the middle, who promised hope but chose pragmatism.

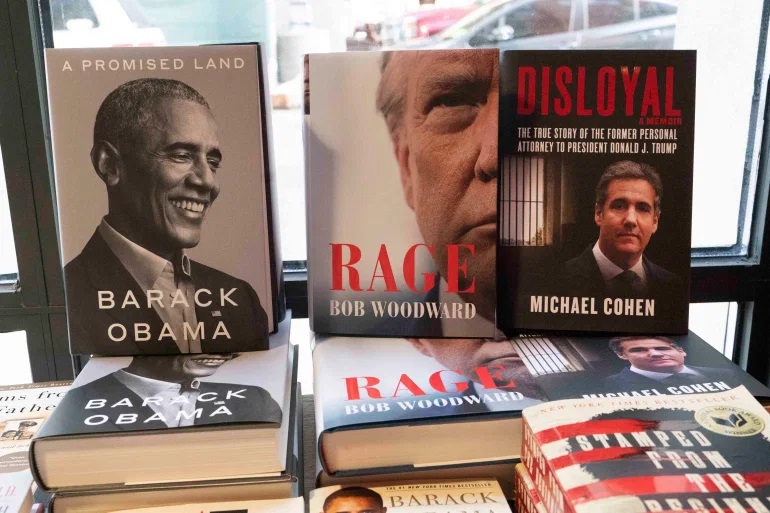

I have long found memoirs of American politicians to be heavy on humbug and light on new insight, especially those meant to pave the way to the White House, like Hillary Clinton’s Hard Choices, Kamala Harris’s The Truths We Hold, Cory Booker’s United, and yes, the best of them, Barack Obama’s The Audacity of Hope.

Since his political career is now behind him, I hoped the former president was going to be a bit more forthcoming, blunt and daring in his new memoir, The Promised Land.

Seven hundred pages into the book, I had mixed feelings or perhaps I was a bit too generous with my hope. Obama may no longer be as hampered by politics, but he is certainly haunted by legacy.

My first impression when reading The Promised Land is that unlike the sitting president, Donald Trump, who is unable to articulate a thought or finish a sentence, Obama is a gifted writer, as he is a brilliant orator.

In fact, the first few chapters show how his personal narrative, story-telling and exceptional oratory, highlighted in his speeches against the Iraq war and his address to the 2004 Democratic National Convention, propelled him to the national political scene. They played a major part in his rise from an Illinois state senator to US senator and then two-term president.

Obama comes across as thoughtful, conciliatory, as well as funny and sarcastic, as if to draw a contrast with his divisive, deceptive, and miserable successor. It is as if the former president remains haunted by the effect of Trump’s victory on his legacy and his attempt to undo everything Obama.PUBLICITÉ

It is indeed telling that he chose to end the book with the killing of Osama bin Laden and his humiliation of Trump at a White House Correspondents’ Association dinner.

Obama may be Trump’s opposite, but not because he embraces Black nationalism the way Trump embraces white nationalism or supremacy. Rather, because he deliberately or instinctively veers towards the middle, always looking for two sides to any issue.

He is the guy directing the traffic, always situating himself at the centre of every argument, between hope and fear, idealism and realism, principles and interests, homeowners and bankers, grieving mothers and army commanders, protesters and police, young advisers and political veterans.

Likewise, internationally, Obama positions himself between the Europeans and the Chinese, say on climate change, between the Palestinians and Israelis, the Arab protesters and allied Arab dictators, almost always rooting for the first while explaining, justifying or even defending the latter.

He carefully juxtaposes writing letters to the grieving families of dead soldiers with his support for a military surge in Afghanistan, accepting the Nobel Peace Prize with escalating war efforts.

He readily reconciles the promise and peril of his own first two years in office, commending his administration’s impressive record while blaming himself for the Democratic losses in the 2010 mid-term elections, writing: “… it proved that – whether for lack of talent, cunning, charm or good fortune – I’d failed to rally the nation, as F.D.R. had once done, behind what I knew to be right.

His critics may see his memoir as the recollections of an opportunist, but it actually is one long expose in defence of pragmatism.

Obama claims to draw inspiration from Mahatma Gandhi, Nelson Mandela, Martin Luther King Jr, and the most revered American presidents, like Abraham Lincoln and Franklyn Roosevelt, who presided over two of the toughest periods of US history.

Whether he will go down in history as one of these transformative leaders is too early to judge. But Obama seems to suggest that his success to get elected, not once but twice, as the first Black president is in and by itself a transformative event for America.

To his credit, Obama comes across, again unlike his successor, as someone humbled by experience and bruised by the democratic reality.

He recognises that the president can change a few US policies while in office, but cannot transform its political culture. He also acknowledges that he lacked the political experience and the political allies, considering he went from a freshman senator to leading presidential candidate within just two years.

Likewise, his knowledge of the world was limited to his childhood in Indonesia and university friendships with international students. Obama hoped that what he lacked in experience he could make up for in hard work and fresh new ideas.

But within two years, the mood in the country had shifted towards the right, deepening the social, political and racial divisions in America.

Likewise, the foreign policy establishment or the Blob, proved powerful, tenacious and set in its ways. He says he came to end the war mindset but found himself constantly undermined by both the military and the civilian establishment, including members of his cabinet.

Obama blames himself for not being forceful enough, dare I say, like Trump. He specifically regrets not having the foresight to push the Democrats to do away with the filibuster – a tactic used to prevent a bill from being voted on – that allowed Republican senators to undermine or even block his agenda with a mere 40 percent of the seats.

But it was not only the Republicans. Obama acknowledges that America suffers from a deeper cultural and racial malady under a dominant (white) political culture that feels threatened by multiculturalism and is hostile to immigrants and foreigners.

Paradoxically, some of the most insightful passages about America’s political culture in the book are the ones he says he thought of but never uttered during his time at the White House.

For example, he writes how the drop in his popularity in the polls after calling a policeman’s attack on a Black man in Boston “stupid”, reminded him “that the basis of our nation’s social order had never been simply about consent; that it was also about centuries of state-sponsored violence by whites against Black and brown people.

Or, how the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill showed, “We Americans love cheap gas and our big cars more than we care about the environment.”

Obama also had more than a few insightful things to say about his predecessor’s blunders in the Middle East, Saudi, Emirati and Israeli warnings and hostility towards the Arab Spring, the domestic repercussion of disagreement with Israel, the reasons for the stalled Middle East “peace process”, and much more.

But that would have to wait for another day.

Marwan BisharaSenior political analyst at Al Jazeera.Bishara was previously a professor of International Relations at the American University of Paris. An author who writes extensively on global politics, he is widely regarded as a leading authority on the Middle East and international affairs.

World Opinions Débats De Société, Questions, Opinions et Tribunes.. La Voix Des Sans-Voix | Alternative Média

World Opinions Débats De Société, Questions, Opinions et Tribunes.. La Voix Des Sans-Voix | Alternative Média